- By: Tom Garside

- In: Teaching Skills

Of the four language skills, speaking is the most important in terms of managing day-to-day classroom interaction. We deliver most of our classes through spoken information, and it is through a spoken activity that learners can show what they can really do with the language they are learning from moment to moment in class.

However, in most mainstream educational settings, class sizes and time constraints tend to preclude the development of authentic listening and especially speaking skills work.

This article will explore the reasons for this, and some ways that teachers can ensure that their students are getting sufficient practice in this important area.

Why is speaking an underdeveloped skill?

There are several reasons why speaking is given low priority in mainstream language education. Firstly, many schools focus on skills to pass exams, and take a product-focused view of language education.

As speaking is typically not tested as thoroughly as other more empirical aspects of language such as grammatical and vocabulary accuracy, reading comprehension and accuracy of written language. More time is devoted to these areas in order to improve test results at the expense of holistic language development.

Secondly, speaking skills are quite difficult to define, and therefore make purposeful.

The accuracy of a spoken repetition drill is relatively easy to assess, but the effectiveness of a discussion, debate or extended opinion is a greyer area.

Many teachers focus on the accuracy of information, which can be quantified and criticised easily, while missing the features of spoken language which make up effective oral communication.

Thirdly, the typical mainstream classroom environment is not designed to facilitate much-spoken interaction.

Desks are often arranged individually, or in pairs facing the same direction, with the focus of the class is often on the teacher rather than the interaction between students, and class sizes of 30+ makes it difficult for a teacher to monitor what is happening during mass speaking tasks.

This makes for a less-than-ideal setting for useful speaking work to take place.

Finally, many cultures of education dismiss free-spoken interaction as academically unimportant compared to paper-based skills such as reading comprehension, essay writing and formalised listening practice.

Authentic, communicative tasks such as discussions, debates and flexible speaking games are seen as just a bit of fun, and therefore not academically valid.

If this view is shared by teachers and students alike, the motivation to speak is greatly reduced, and less focus is given to speaking development.

Speaking as evidence of learning

Far from being invalid to the learning environment, student speaking is probably the best indicator of what learners are taking on from their learning experience. Speaking is performed in real-time, spontaneously and (usually) without long periods spent planning the message.

This means that when students are asked to speak out using examples of any grammar, vocabulary or comprehension points, they are showing the teacher their real level of understanding at that moment.

This is invaluable for teachers, as they can then respond appropriately, ensuring that all students are brought to the same level of comprehension and usage throughout a lesson.

Calling on students to lead answer sessions, asking students to discuss their answers before final confirmation of ideas, and responses to elicitation of new language may be daunting for students at first, but as they get used to this routine as a method of co-managing the interaction in the classroom, they will quickly take more opportunities to speak with confidence and participate more openly.

A couple of weeks of awkward silences is worth persevering with, in order to develop a more interactive environment where speaking work is incorporated into all areas of your students’ language study.

Also Read: 5 Tips for teachers to sharpen their listening skills

Keeping speaking work purposeful

The everyday use of student talk as a teaching tool in this way is one teacher-focused purpose for bringing more spoken interaction into the classroom, but if you want to develop students’ speaking skills specifically, start by defining what specific speaking outcomes you are working them towards.

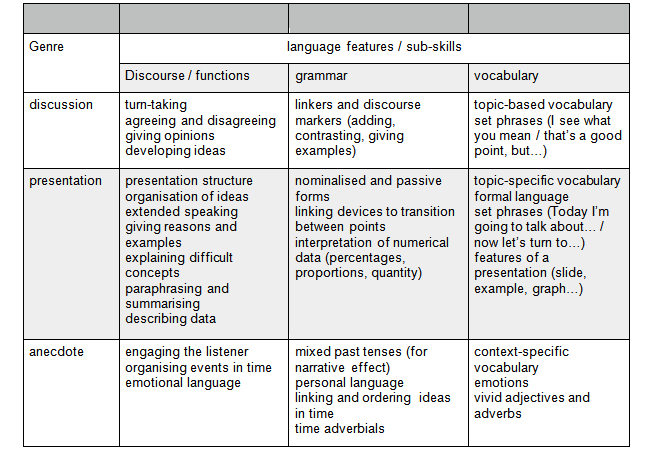

Different genres of speaking involve different language features; presentations are very different from debates and discussions, we expect different types and lengths of turns from participants, and different types of development of ideas as the speaking event unfolds.

Defining a clear genre for speaking activity helps to add purpose to student talk. By planning the component features that we expect from this genre, defining language points which relate to the topic, and leading practice sessions in these areas before the final event are all good techniques for genre-based speaking.

Speaking as a language skill

The production of any form of spoken language involves a lot of different types of cognitive, socio-linguistic, strategic and linguistic processing, whether we feel it or not as we communicate.

The enormous and complex language skill of speaking needs to be broken down into its component sub-skills, which can be worked on one by one to develop effective use of appropriate language in specific settings.

Students should be made aware of which aspects of their speaking they will be working on, and how they will be asked to do this during a lesson. Moving from the type of speaking event they will practice to the specific skills that the activity will develop is a good technique, as outlined below:

Sub-skills of speaking – teaching ideas, activities

There are many simple speaking tasks which can be used to teach these sub-skills of speaking before students are asked to perform in larger activities. Some simple preparatory games and tasks are outlined below:

Extended speaking: timed, topic-based speaking

Students are given a topic card containing 4-5 keywords that they must use in a timed speech on that topic, for example: Traffic – private cars, public transport, pollution, congestion.

- Students must speak for an allotted time (2-3 minutes) on that topic, using those keywords in groups.

- Listeners in the group must guess the keywords according to the speech given.

- Extend the time to extend the production of language, incorporating more of the students’ own ideas as they work to fill the time.

Paraphrasing and circumlocution: Just a minute

Based on the famous Radio 4 quiz show, students must speak for as long as possible on a random topic (spoons, baseball, dogs…) without repeating any single word, hesitating with silence, or outright lying.

- Listeners keep their ears open for these and shout when they hear something wrong.

- A correct challenger picks up the same topic where the first speaker finished, until one minute is up – whoever is speaking at the end of the minute wins the round.

Structured discussion: Function cards

Helping students to organise their ideas with speaking function cards can give more structure to interaction.

- Put a pile of cards with functions such as ‘agree’, ‘disagree’, ‘example’ or ‘contrast’ in the middle of a group of students, who have to discuss a given opinion for five minutes.

- The first student introduces the topic, and the next student picks up a card, continuing the discussion with that kind of information.

- Go around the group until everyone has spoken or the cards have all been taken, and the last student must summarise the discussion as they had it.

Also Read:

- Activities to increase student talk time

- Using tests as a teaching tool for all-round language development

Conclusion:

Whichever activity you use to practice these sub-skills, remember that students need input into what kinds of phrases they can use to do these jobs, and how to pronounce them, before they attempt the task. These are practice activities, so do not teach students how to structure their ideas, they just provide a framework for them to start putting this into practice.

Good luck planning and delivering more focused speaking activities with these in mind!

Please Share:This article was originally published on August 26, 2019 and was last updated on January 28, 2020.

Courses We Offer:

1. CertTESOL: Certificate in TESOL

A level 5, initial teacher training qualification for new and experienced teachers, enabling you to teach English anywhere in the world. The course is equivalent to Cambridge CELTA.

Learn More

Developed by our Trinity CertTESOL experts, for a comprehensive, self-paced learning experience. Earn an internationally recognized certificate and master essential teaching skills, accessible globally 24/7.

Learn More